- Home

- Charlie Higson

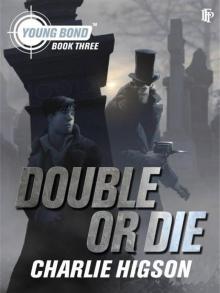

Double or Die Page 11

Double or Die Read online

Page 11

The taxi had no option but to stop. It was either that or run James down. The driver was a fat, red-faced man with a big nose.

‘You’re out late,’ he said, winding down his window. ‘Or are you up early like me? You’re my first passenger of the day. Hop in.’ He stretched an arm out to open the back door and James gratefully climbed aboard.

‘Where to, mate?’ said the cabbie, as he pulled out and moved off.

‘Regent’s Park,’ said James twisting round in his seat to look back. The men had stopped on the pavement and were sullenly watching the taxi drive away.

‘A bit young to be out at this time of night, aren’t you?’ said the cabbie, glancing in his mirror.

James didn’t have the energy to face any awkward questions and wondered whether he should get out of the cab the next time it stopped at a junction. But it was warm and dry in here and he had had enough of the streets. He said nothing, and pulled the stolen coat around his thin body, tipping his head forward to shade his face.

‘It’s none of my business,’ the cabbie went on. ‘But if you’re in any kind of trouble –’

‘You’re right,’ said James, interrupting. ‘It isn’t any of your business.’

‘No need for that,’ said the man. ‘I was only going to say that maybe I can help. I know times are hard at the moment. There’s all sorts of people out on the streets. Have you got somewhere to stay?’

‘I’ve come to London to visit a friend,’ said James. ‘In Regent’s Park.’

‘You’re a bit out of the way, aren’t you?’

‘I got lost. I’ll be fine once I get there.’

But would he be? What if Perry wasn’t home? James had no money and there was nowhere else to go.

‘I know this city well,’ said the cabbie. ‘London town. You’d be amazed the things I’ve seen. The stories I could tell. The passengers I’ve carried. You’ve a story. I know that much. Maybe you want to tell it to me, maybe you don’t. And I suppose you’re right. It is no business of mine. I’ll drop you off in Regent’s Park and probably never see you again. You’ll just be one more lost soul in a city of lost souls.’

James certainly felt like a lost soul. He stared out of the window at the endless passing streets of London. He couldn’t begin to imagine how many people there were living in the city. There was house after house, in long grey rows. One or two had Christmas wreaths on the doors and decorations in the windows. He was swallowed up in a black shadow of sadness. Christmas hadn’t been the same since his parents had died. He always enjoyed Christmas Day in his Aunt Charmian’s little cottage in Kent, but it wasn’t the same. In a sense he knew that he would always be alone in the world.

Perhaps he’d got involved in this crazy adventure to take his mind off the emptiness he always felt at this time of year, when the dark days deepened his sense of loss.

He shook himself and wiped his face.

Don’t ever stop and think, James, just keep moving.

‘Nearly there, son,’ said the cabbie and James looked back out of the window.

They were passing a row of dreary, faceless buildings with names like ‘Transco Trading’, ‘Alliance Holdings’, ‘The Minimax Fire Extinguisher Company’ and ‘Universal Export’, then they turned off the busy main road and the commercial buildings were replaced by trees.

They were in Regent’s Park.

It had stopped raining and there was the faintest glimmer of light in the sky, but the day was still flat and grey and lifeless. The park was ringed by elegant, cream-coloured terraces in a classical Greek style. Many had grand porches held up by pillars.

James had always known that Perry’s family was rich, but he had never really thought before about the difference between the two of them. James was perfectly happy living in the little cottage in Kent and couldn’t imagine what it would be like to live in such a large, imposing house. He was not sure that he would like it.

They found Perry’s address – a house on Cumberland Terrace, overlooking the green expanse of the park.

The cabbie pulled up to the front steps.

‘I shall have to borrow some money from my friend,’ James explained. ‘It was further than I imagined.’

‘Don’t try running off cos I’ll come after you,’ said the cabbie, though in an almost friendly way. ‘I may not look very nimble, but believe you me, I’ve had plenty of practice chasing fare dodgers.’

‘I won’t run off,’ said James, although he had been planning on doing just that if Perry wasn’t at home.

He went up the steps to the huge, black front door and pulled the bell.

Nothing happened. James heard no ring in the house and there were no signs of life. In fact, it was quiet as the grave. He pulled the bell again and waited, his heart thumping.

Again nothing.

He turned round. The taxi driver was watching him, the smile on his face slowly dying.

James gave him a reassuring wave and wondered just how fast the man could run.

11

Scrambled Eggs

James was just about to sprint off down the street when the door swung inwards and there stood a bleary-eyed servant, who had obviously dragged on his uniform in a hurry. He peered at James, who was all too aware what he must look like: a boy in a too-large overcoat, wearing no socks and with a hat pulled down over a fresh bandage on his forehead.

‘Good morning, can I help you?’ said the man, straining to appear civil.

‘Good morning,’ said James, as politely as he could. ‘I’m a friend of Perry’s.’

The man sighed and rubbed his face. ‘I rather thought you might be.’

‘Is he at home?’ said James.

‘He’s asleep,’ said the servant, who had dropped any attempt at politeness now.

‘He sleeps no m-more!’ came a cry from inside the house and Perry appeared in dressing gown and slippers. ‘Strike m-me pink,’ he said when he saw James. ‘What the devil happened to you?’

‘I’ll explain in a minute,’ said James. ‘But I need to pay a taxi and I have no money.’

‘Braeburn,’ Perry said, clapping the servant on the shoulder, ‘be a good chap and pay the m-man, would you?’

Braeburn muttered and grumbled as he shuffled down the steps, pulling a purse from his jacket, and Perry took James inside.

‘Come with m-me,’ he said. ‘You look like a fellow sorely in need of some breakfast.’

Perry led James through a vast entrance hall, with a marble floor and a wide staircase curving upstairs. There were family portraits on the walls, but the few pieces of furniture were covered with dustsheets and the place felt chilly and unlived-in. James remembered that Perry’s family was away, so the house must have been shut down for the winter.

‘We’ll fill your tank,’ said Perry, taking James down a servants’ staircase. ‘Then you can tell m-me just exactly why you abandoned m-me in the city of dreaming spires.’

‘Actually,’ said James, wearily, ‘I think you’ll find that’s Oxford.’

‘What is?’

‘The city of dreaming spires.’

‘Well, I saw a fair few spires in Cambridge,’ said Perry, ‘and they looked pretty dreamy to m-me, but that’s not the point. The point is – what the hell happened? I waited for you and when you hadn’t shown up I toddled off to Trinity. When I arrived, there was some sort of commotion going on at the porter’s lodge, a young m-man was there with a police-m-man.’

‘We must have missed each other,’ said James. ‘I didn’t exactly come back by a direct route.’

They had arrived in a large kitchen at the front of the house below street level. There was a range here, big enough to cook for a whole football team, and it warmed the room deliciously.

‘When I got back the m-motor had gone,’ said Perry indignantly. ‘And the woman in the cafe told me you’d been asking after m-me, nice of you to dump m-me like that, I m-must say, I had to get the train back.’ Perry stopped and looked at James. He

frowned and sighed. ‘Where have you been, James?’ he said kindly. ‘I’ve been worried sick.’

‘It’s a long story,’ said James, sitting down by the range. He pulled off his shoes and pressed his feet against one of its warm, metal doors. ‘And I need some food inside me and a cup of strong coffee before I can start it.’

‘I propose scrambled eggs,’ said Perry. ‘Not least because it’s the only thing I can cook.’

Perry put a jug of coffee on to heat up, placed two slices of bread under a grill, then found some eggs and began to noisily whisk them in a bowl.

James watched hungrily as Perry tossed the eggs in a pan with some melted butter and stirred them till they were ready. A sudden thought struck him and he began to laugh.

‘What’s so amusing?’ said Perry.

‘Scrambled eggs,’ said James.

‘What about them?’

‘It’s the answer to a crossword clue.’

‘What do you m-mean?’ said Perry. ‘What was the clue?’

‘The one I asked the fake Gordius to solve at the Crossword Society meeting,’ said James. ‘It was simply the letters “GSGE”. It’s a sort of riddle and I’ve just worked out the answer. It’s “Scrambled Eggs”.’

‘I don’t get it,’ said Perry.

‘It’s the word “eggs” all scrambled up,’ said James.

‘It’s all beyond m-me,’ said Perry as he put the toasted bread on a plate and scraped the eggs on to it.

James sat at the table and ate slowly and steadily until every last scrap of food was gone from his plate. At last he sat back with a great sigh and wiped his lips. ‘That was the best meal I have ever eaten,’ he said.

Perry smiled and passed James a mug of coffee. ‘Now, your side of the bargain,’ he said. ‘I can wait no longer.’

And so James told his story, from finding Peterson dead in his study, through the car chase across Cambridgeshire, to waking up in the hospital. For once Perry was silent, listening intently. It was only when James finished, with his arrival on Perry’s doorstep, that he finally spoke up.

‘If I didn’t know you better, James,’ he said, ‘I’d suspect you of m-making it up. You have a terrible habit of attracting trouble. You are a m-magnet for danger. What a m-mess. What are we going to do, now?’

‘God knows,’ said James. ‘I haven’t a clear thought in my head. Maybe the coffee and eggs will help, but I’ve been terribly confused, Perry. I can’t tell you how glad I am to see you.’

‘And m-me you,’ said Perry, sitting down opposite James and smiling at him.

‘The whole thing’s a mess,’ said James.

‘As I see it,’ said Perry, ‘we have two options. Either we go straight to the local police station and tell them everything, then face the m-music, or the other option, which I m-must say is m-my favourite, we bury our heads in the sand like a couple of peacocks and let the police sort it out without our help.’

‘Ostriches,’ said Bond. ‘Not peacocks.’

‘You can be an ostrich if you like,’ said Perry. ‘I’d m-much rather be a peacock. All those feathers.’

James laughed. He was still feeling light-headed and slightly hysterical. ‘Can’t you ever take anything seriously?’ he said.

‘I try not to,’ said Perry, and then his face dropped and he became thoughtful. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I wish I knew what to say. I can’t take all this in, James. I really would prefer to go somewhere far away and hide till it was all over.’

‘Is it right, though?’ said James. ‘Not telling anyone?’

‘We need to think about saving our skins,’ said Perry. ‘They’ll have found Peterson’s body by now, m-maybe they can start piecing it all together themselves.’

‘Except I took what might be the only clue,’ said James.

‘The letter,’ said Perry. ‘Do you still have it?’

‘No,’ said James, and he groaned. ‘It was in my coat pocket with the photograph of Peterson and Fairburn. I lost it with my coat in the river.’

‘You re-m-member what it said, though?’

James closed his eyes and thought hard. He imagined himself back in the cafe, reading the letter under the table. He pictured the words on the page and slowly they formed in his mind. ‘Dear John,’ he said. ‘I have heard nothing from either you or Alexis since I came to see you in Berkeley Square the other day. I know you told me not to panic. I know you assured me that Alexis would be all right and that we needn’t involve the police, but I am very worried about him…’ He stopped and opened his eyes. ‘That’s about all there was.’

‘If we knew who this John chap was,’ said Perry, ‘we could go and visit him in Berkeley Square.’

‘John Charnage,’ said James.

‘How do you know that?’ asked Perry.

‘The photograph,’ said James. ‘There were three friends in the photograph: Fairburn, Peterson and a third man called John Charnage. I’m sure he’s the John the letter’s written to.’

‘The one in the suit of armour, Sir Lancelot?’ said Perry.

‘Yes,’ said James.

‘Now we’re getting somewhere,’ said Perry. ‘Let’s pour some m-more coffee inside you and see if you don’t turn anything else up.’ He refilled James’s coffee cup, than sat back down at the table.

‘Did you lose anything else in the river?’ he asked.

‘I don’t think so,’ said James.

‘What about the other piece of paper?’ said Perry. ‘The one with the code on it? Do you still have that?’

‘I hope so.’ James tore off his shoe and opened the heel. There, tucked snugly inside, was the note. The outer layer was slightly damp, but the water hadn’t penetrated far beyond it.

It was still legible.

James unfolded it and flattened it on the scrubbed surface of the kitchen table.

‘What do make of it?’ he asked.

Perry studied the rows of ones and zeros. ‘No idea,’ he said. ‘M-maths was never m-my strong point.’

‘Nor me,’ said James. ‘The person we need to show this to is Pritpal. He’s a genius with numbers.’

‘We should go and visit him at the Eton M-Mission,’ said Perry. ‘We could be there in half an hour.’

‘First we go to Berkeley Square,’ said James, ‘and find John Charnage. He obviously knows something about what’s going on. He’ll be able to help us.’

‘You see,’ said Perry. ‘Now we have a plan and things don’t seem so bleak. But you’re not going out like that, you look like a scarecrow.’

James looked down at his shabby ill-fitting clothes, and the pyjama jacket he was wearing as a shirt.

‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘I’m really not sure I could turn up in Mayfair looking like this.’

‘I’ll dig out some old clothes of m-mine,’ said Perry. ‘And I think you could do with a bath as well.’

They went by a back staircase up to the second floor where there was a large, unheated bathroom with a cast-iron bath in it, spotted with rust.

Ten minutes later James was lying on his back staring at the ceiling, which was cracked and stained with mould. He half-floated in the muddy-looking water and tried to empty his mind and think of nothing. He closed his eyes for a moment and felt sleep tugging at him. He tried to fight it but must have nodded off, because the next thing he knew he’d slipped under the water.

He woke with a start, coughing and spluttering, washed himself quickly and got out of the bath.

Perry had given him a three-button aertex shirt, a dark-blue worsted suit and some fresh underwear. He found that they fitted him rather well. Once dressed, he carefully removed the bandage on his forehead and inspected the damage in a mirror over the sink.

There was some bruising, but the cut wasn’t as bad as he had feared. He pulled his hair forward with his fingers and arranged it over the wound. He was pleased with the result. The bandage had been too conspicuous. Now you could barely see anything.

He was r

eady.

It was nine o’clock by the time James and Perry pulled up in a taxi in Berkeley Square. The boys got out and Perry paid the driver.

The square was larger than James remembered. Tall houses stood on all sides and there was a garden in the middle, surrounded by iron railings. Several tall plane trees grew here, looking stark and gaunt without their foliage.

Thin, watery light filtered through the low clouds in the gunmetal-grey sky. The rain was still holding off, but Perry had taken the precaution of bringing an umbrella, which he swung about flamboyantly, its metal tip clacking on the pavement.

‘Where do we start?’ said James, who had no way of knowing in which of the many houses John Charnage might live. ‘To knock on every door would take all day.’

‘I suppose we shall have to ask someone,’ said Perry, who was utterly unembarrassed by this sort of thing.

The square was quiet at this time on a Saturday morning, but they spotted a grocery delivery cart, the horses standing tied to some railings. A grocer’s boy was approaching the back of the cart carrying an empty basket. Perry strolled over and asked him if he perhaps made deliveries to a Mr John Charnage. The boy sniffed and looked blank.

Perry dug around in his pockets and fished out a handful of coins that he handed to the boy with a wink.

‘John Charnage?’ Perry repeated. ‘Do you know him?’

The boy glanced around the square. There was nobody else about.

‘We do all the deliveries round here,’ he said proudly, then nodded down the street. ‘Charnage’s gaff is that one over there in the corner. Nice man, but doesn’t always pay his bills on time.’

Perry thanked the boy and made his way with James towards an ugly grey-brick house. No light showed in any of the windows, some of which still had the curtains drawn.

Perry walked up to the front door and tried to peer in through the frosted-glass windows.

‘Looks dead in there,’ he said and then nearly fell over as the door swung open.

A butler whose immaculate uniform was straining to contain his bulky, muscular body, stood there. He had a shaved head and the flattened nose of a boxer.

The Dead

The Dead The Sacrifice

The Sacrifice The Fallen

The Fallen The Fear

The Fear The Enemy

The Enemy Blood Fever

Blood Fever Double or Die

Double or Die Young Bond, The Dead

Young Bond, The Dead The Hunted

The Hunted Hurricane Gold

Hurricane Gold Geeks vs. Zombies

Geeks vs. Zombies The Hunted (The Enemy Book 6) (Enemy 6)

The Hunted (The Enemy Book 6) (Enemy 6) The Beast of Babylon

The Beast of Babylon