- Home

- Charlie Higson

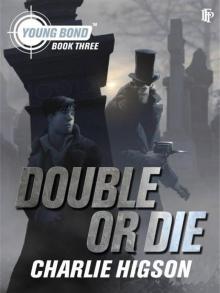

Double or Die

Double or Die Read online

YOUNG BOND BOOKS BY CHARLIE HIGSON

SILVERFIN

BLOOD FEVER

DOUBLE OR DIE

HURRICANE GOLD

BY ROYAL COMMAND

DANGER SOCIETY: YOUNG BOND DOSSIER

SILVERFIN: THE GRAPHIC NOVEL

DOUBLE OR DIE

CHARLIE HIGSON

Ian Fleming Publications

IAN FLEMING PUBLICATIONS

E-book published by Ian Fleming Publications

Physical books available from:

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Disney-Hyperion Books, an imprint of Disney Book Group, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690

Ian Fleming Publications Ltd, Registered Offices: 10-11 Lower John Street London

www.ianfleming.com

First published by the Penguin Group 2007

Copyright © Ian Fleming Publications, 2007

All rights reserved

Young Bond and Double or Die are trademarks of Danjaq, LLC, used under licence by Ian Fleming Publications Ltd

The moral right of the copyright holder has been asserted

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-1-906772-63-5

For my dad

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Sandy Balfour and John Halpern for guiding me through the world of cryptic crosswords and helping with clues. And to Simon Chaplin at the Royal College of Surgeons

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Acknowledgements

The Hungry Machine

Part One: FRIDAY

1 Thoughts in a Bamford and Martin Tourer

2 Stevens and Oliver

3 The Raid on Codrose’s

4 Apex X

5 Gordius

6 Shoot the Moon

7 A Lovely Wreck

8 See Cambridge and Die

9 The Smith Brothers

Part Two: SATURDAY

10 The Big Smoke

11 Scrambled Eggs

12 A Clarinet Sang in Berkeley Square

13 Breaking the Code

14 Soft Tissue

15 It’s Your Funeral

16 Carcass Row

17 Paradice

18 What’s Your Poison?

19 A Volatile Substance

Part Three: SUNDAY

20 The Monstrous Regiment

21 The Knight Who Did a Deal With the Devil

22 The Pneumatic Railway

23 Into the Lion’s Jaws

24 Nemesis

25 The Empress of the East

26 Babushka

27 Wake Up or Die

28 Out of the Fog

29 The Eyes of a Killer

The Hungry Machine

The human brain is a remarkable object. It contains a hundred billion neurons, all talking to each other via tiny electrical sparks, like a never-ending fireworks display inside your skull.

Your brain weighs three pounds. It makes up only one-fiftieth of your body, yet it uses up over a fifth of your blood supply and oxygen.

The brain is a hungry machine. It never shuts down. Even while you are asleep it is awake, keeping your lungs breathing, your heart beating, the blood flowing through your veins. Without your brain you can do nothing. It allows you to ride a bike, read a book, laugh at a joke. It can store a whole lifetime of memories.

But it is very fragile.

Alexis Fairburn was painfully aware of this, because there was a pistol pointing at his head, and he knew that if that gun were fired, all those precious memories, that he had been storing up for the last thirty-two years, would be blasted into oblivion. Then his lungs would fall still. His heart would stop pumping. The blood would freeze in his veins and Alexis Fairburn would cease to be.

The pistol was a six-shot revolver with a short, stubby barrel. Not very accurate at long range, but deadly enough close up. What made it more deadly was its grip, which doubled as a knuckleduster. The fingers of the man holding it were curled through big brass rings. One punch would shatter a man’s jaw.

Fairburn knew that this type of gun was called an Apache, after the vicious street thugs who had carried them in Paris at the end of the last century. Their weapons had also carried blades that swung out and could be used like bayonets.

He sometimes thought he knew too much.

And even as he stared at the nasty black hole in the gun’s nose he heard a click, followed by a metallic scraping sound, and a four-inch-long, spring-loaded stiletto blade slid out from beneath the barrel and snapped into place.

Sometimes Fairburn wished that he could be happy and stupid, blissfully unaware of everything that was going on in the world around him. Sometimes he wished that, instead of spending half his life expanding his brain and filling it with facts and figures, he had devoted some of that time to his body. In moments like this he wished that he had big muscles and quick reflexes. If only he had learnt how to disarm a man he might now be able to grab his attacker’s wrist and wrestle the gun out of his hand, maybe even turn it on him. He had read about such things. He knew in theory that it could be done, but he also knew that it would be useless to try. He was weak and he was timid and he was clumsy.

Now that he thought about it, however, he realised that he wasn’t scared.

That was interesting.

He would have assumed that he would be terrified. But, no, all he felt was disappointment. Regret that his remarkable brain was soon to be switched off.

‘Don’t try to run, or resist in any way,’ said the gunman and, for the first time, Fairburn looked at him, rather than at his gun. He was tall and thin and stooped, with a huge, bony head that looked too heavy for his shoulders. His large black eyes were set in deep hollow sockets and the skin was pulled so tight on his head that it resembled a skull.

The gunman was not alone. He had an accomplice, a younger man with a pleasant, unremarkable face. He wouldn’t have looked out of place behind the counter in a bank, or scribbling away at a ledger in an office. Fairburn found that it helped to think of him as a clerk rather than as a potential assassin. It made him less threatening.

‘You know what will happen if he pulls that trigger?’ said the clerk with a hint of menace.

The menace was unnecessary. Fairburn knew exactly what would happen. The hammer of the gun would snap forward and strike the percussion cap at the rear of the bullet casing. This would set off a small explosion which would propel the shell at twenty-five feet per second out of its casing and down the barrel, where a long spiral groove would cause it to spin, so that it would fly straighter. Finally, it would burst out of the gun, not six inches from Fairburn’s forehead.

The bullet would be soft-nosed, designed to stop a man. As it hit bone it would flatten and widen like an opening fist and then it would tunnel through his head, sucking out any soft matter as it went.

A bird sang in a tree nearby. Fairburn knew from its song that it was a chaffinch. He glanced up and saw that it was sitting on the branch of a yew tree. It was a British custom to plant yews and cypresses in graveyards. A custom they had adopted from the Romans. It was also a Roman custom to put flowers on a grave.

Fairburn sighed. His brain was full of such a lot of useless information.

‘What are you looking at?’ said the clerk.

‘I’m not looking at anything,’ said Fairburn. ‘I’m sorry. I was distracted.’

‘I wou

ld advise you to pay attention.’

‘Yes. I do apologise,’ said Fairburn. ‘But might I ask what exactly you want me to do?’

‘We would like you to accompany us, Mister Fairburn,’ said the gunman.

So they knew his name. This was not a random attack. They must have followed him here. But what did they want?

Fairburn thought hard, casting his mind back over the day. What had happened? Who had he met? What had he said that would cause these two men to be here in the middle of Highgate cemetery, with one holding an Apache to his head?

Up until now it had been a fairly ordinary Saturday. He had followed the same routine that he had been keeping to for the last few weeks. He had driven up to London first thing from Windsor, visited the Reading Room at the British Museum, then had lunch at his favourite restaurant in Fitzrovia, and finally he had come here to the cemetery, where he had been making sketches and jotting down notes for a book he was planning to write on eminentVictorian scientists, several of whom were buried here.

The last thing he had done was to take a rubbing from a headstone with an interesting inscription. He had forgotten to bring any rubbing paper with him and had been forced to use the back of a letter from his friend Ivar Peterson. He still took a childlike delight in rubbing the wax over the paper and watching the writing form. He had just finished and was putting the neatly folded letter back into his coat pocket, when the men had appeared. They had walked briskly up the path, nodded a friendly greeting and the next thing he knew the ugly snout of the pistol was in his face.

Peterson. Of course. This must be to do with him. Or, more precisely, to do with what Peterson had written about in the letter.

This was to do with the Nemesis project.

He realised that he still had the letter in his hand, hidden inside his pocket. Perhaps he could drop it somewhere. It would be some small clue that he had been here, and, if anyone read it, they might be able to help him.

Idiot.

It would be meaningless to anyone else. Unless somehow he could direct the right person here, someone who could understand what it meant.

Good. His mind was working. He gave the paper one more fold and squeezed it tightly into the palm of his hand.

‘We are going to walk you to your motor car,’ said the clerk. ‘Calmly and casually, like old friends. Then you will drive my brother and I to our destination. We will advise you of the route along the way. The gun will be trained on you at all times, and if you do not follow our precise instructions, we will not hesitate to shoot you. Another colleague of ours will be following in your own motor car. Is that clear?’

‘Perfectly,’ said Fairburn, treading on one end of his shoelace and feeling it come undone. ‘But I still don’t know what you want of me.’

‘For now you don’t need to know,’ said the gunman. ‘Just walk.’

Fairburn took a step and then stopped. ‘My lace,’ he said, looking down at his shoe.

‘Tie it,’ said the young man.

‘Thank you,’ said Fairburn. He crouched down and carefully slipped the piece of folded paper up inside the bottom of his trouser leg. If he dropped it now it would be easily spotted, but this way he could delay it until the men were distracted again.

He straightened up.

‘All set,’ he said, as cheerily as he could manage.

He glanced around at the cemetery, taking a last look and imprinting the images on his brain. He looked at the statues and crosses, and at the gravestones, standing beneath the trees, many overgrown and neglected. Then he took his first step, brushing against some low winter foliage, and, as he did so, he shook his leg and felt the scrap of paper fall out. He didn’t look down to check, but he prayed that it would be lying hidden by the side of the path.

It wasn’t much to go on, but it was all he had. All the hope in the world.

His heartbeat skipped and he felt a tingling in his scalp.

He had lived a dull and secluded life with very little danger and nothing to disrupt the even flow of his days. He was experiencing a new emotion, now, excitement. In a way, he was even enjoying it.

He still had his brain. He must use it somehow to escape from his predicament. He was confident that he would think of something. There wasn’t a problem in the world that couldn’t be solved with brainpower.

You just had to make sure that you kept your brain inside your head.

Part One: FRIDAY

1

Thoughts in a Bamford and Martin Tourer

James Bond was sitting in the passenger seat of his uncle’s Bamford and Martin tourer wrapped in a heavy winter overcoat, his face masked with goggles and a scarf.

His friend Perry Mandeville, similarly dressed, was at the wheel. It was too cramped and awkward to drive with the rain cover up, so they were completely exposed to the grisly December weather. They didn’t care, though, they were on the open road and, despite the icy wind buffeting them, they felt reckless and free.

The car had belonged to James’s uncle who had left it to James when he died. James kept it secretly at the school. Perry had always dreamt of taking it out on the road but James had never let him before today.

This was an emergency.

Perry drove well, but fast, and James had to constantly remind him to keep his speed down. There was very little traffic on the road, but they still had to be careful. They didn’t want to risk being stopped by a police patrol or, worse still, crashing into a ditch.

Perry was older than James, but not yet seventeen, which was the minimum driving age. If anyone found out what they were up to they would at best be beaten soundly and thrown out of Eton, and at worst thrown into jail.

But James wasn’t thinking about any of that. He was filled with a burning excitement. He needed the thrill of danger. It was only on an adventure like this that he came alive. His day-to-day life at school felt grey and dull, but now the boredom had lifted and all his senses were heightened.

That didn’t mean that he could be careless, however. The goggles, hats and scarves were as much worn as disguises as to shield the two boys from the cutting wind.

They were speeding away from Eton towards Cambridge having left a pack of lies behind them. A pack of lies that could soon be snapping at their heels if they didn’t watch out.

James thought back to when this had all begun.

It had been the end of the summer holidays, a few days before James was due to return to Eton. He had been helping out at the Duck Inn in Pett Bottom, the village where he lived with his Aunt Charmian. He earnt a bit of pocket money there washing barrels and stacking crates of empty bottles behind the pub. He was rolling an empty barrel across the ground when he looked up from his work and saw a black car driving through the fields.

He straightened up and followed its progress.

There was a chill in the air and he shivered. The summer was nearly over.

The car slowed as it approached the pub and stopped. The window was wound down. James recognised the familiar face of his classical tutor, Mr Merriot, the man responsible for his education at Eton. With him was Claude Elliot, the new Head Master. They both looked rather serious.

‘Climb aboard,’ said Merriot, and he tried to force a friendly smile on to his face, his unlit pipe wobbling between his teeth.

James got in.

‘Do you know why we are here, James?’ asked Merriot kindly.

James nodded. ‘I’ve been expecting a visit since I talked to you at Dover, sir.’

Earlier in the summer holidays James had gone on a school trip to Sardinia with two masters, one of whom had turned out to be a criminal. Both masters had been killed and James himself had nearly lost his life. When he came home, James had been met by Mr Merriot straight off the boat, and had told him everything that had happened. At the time Merriot had asked James not to breathe a word about it to anyone else. Now it looked like the Head Master had come to make sure that the secrets would remain buried.

James sat in th

e back of the car between the two men feeling hot and stuffy.

‘We have been talking about what happened in Sardinia,’ said the Head, a tall man with round, wire-framed spectacles whose hair was receding at the temples, leaving only a thin strip down the centre of his high forehead. ‘And we think it is for the best if you never speak about these things,’ he went on, ‘not at home, not at school, not anywhere. We would prefer it not to get out that one of our masters was a bad sort.’

James sat in silence. He just wanted to forget about the whole episode and be a normal schoolboy again.

‘We shall stick to the story that the locals have given out,’ said Mr Merriot.

‘What story is that, sir?’ said James.

Merriot sucked his pipe. ‘The official line is that there was an accident,’ he said. ‘A dam burst and both Mister Cooper-ffrench and Mister Haight died in the flood that followed.’ He paused before adding, ‘They both died a hero’s death.’

James smiled a brief, bitter smile before nodding.

‘The truth must never come to light,’ said the Head.

‘I understand,’ said James, although he thought it was terribly unfair that an evil man should be remembered as a hero. But, if it meant that he wouldn’t have to deal with endless questions from curious boys, and newspaper reporters, and people pointing at him in the street, he would go along with the lie.

‘I won’t tell anyone,’ he said.

‘This is the end of it, then,’ said the Head, his face brightening. ‘None of us will ever talk of this again. And, James?’

‘Yes, sir?’

‘From now on you must live a quiet life. Will you promise me that you will stay out of danger? Keep away from excitement and adventure.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Good.’ The Head slapped him heartily on the knee. ‘Thank you, James, I hope that it will be some time before our paths cross again.’

The Dead

The Dead The Sacrifice

The Sacrifice The Fallen

The Fallen The Fear

The Fear The Enemy

The Enemy Blood Fever

Blood Fever Double or Die

Double or Die Young Bond, The Dead

Young Bond, The Dead The Hunted

The Hunted Hurricane Gold

Hurricane Gold Geeks vs. Zombies

Geeks vs. Zombies The Hunted (The Enemy Book 6) (Enemy 6)

The Hunted (The Enemy Book 6) (Enemy 6) The Beast of Babylon

The Beast of Babylon